Of the various ways to filter the internet, manipulating DNS is probably the simplest and cheapest in terms of resources. DNS, the Domain Name Service, is the mapping between the human-readable URLs that we use, like https://www.pseudonymity.net, and the more machine-friendly IP addresses, like 87.106.104.43.

The Chinese Golden Shield Project, or Great Firewall, famously makes use of a range of techniques. These include keyword filtering, as reported by Clayton et al., as well as active blocking of services such as Tor at the IP level, and more manual censorship and takedown on services like Weibo.

In the past year or so I’ve spent some time tinkering with exactly how China’s internet is filtered. In particular, I’ve been interested in the extent to which the system is centrally-driven, with blanket country-wide decisions and implementation, against how many of its decisions are loose and locally applied by regional authorities and ISPs.

To study this it is more or less useless to fire up a VPN, or a copy of Tor, and run network tests. Filtering conditions may vary by ISP, by province, by city or by ISP. When I see a report that some site ‘is blocked in China’, my immediate response has become to ask where. On which ISP? Using what method?

Instead, we need to study internet filtering with enough resolution to capture a potentially complex and varied filtering landscape. Multiple systems across the country, on different networks, must be collated and compared. From my personal research bias and interests, I’m interested in how this can be achieved remotely. I’ve presented work on this elsewhere, (see my FOCI paper), but I’m concerned with the approach of asking users to install censorship monitoring software on their systems when those users are often not technically qualified to understand the risks. I don’t genuinely understand the risks of accessing http://www.tibet.net from inside China, and I can’t justify asking another, probably less informed, user to do it on my behalf.

As a result, to date I’ve focused largely on looking at how China poisons DNS. DNS poisoning is a common and relatively simple way to stop people reaching web pages, provided that you’re happy to block the entire domain. DNS servers are relatively common, and also are usually open to requests from anywhere, meaning that it’s easy to get wide coverage at a relatively high resolution.

The short version of the results are that poisoning is rife across China, with Twitter being the most widely poisoned domain. The most common type of poisoning is to misdirect by providing an incorrect IP address, rather than to claim that a given domain does not exist.

In general the majority of this IP misdirection seems to be more or less random. Users attempting to reach sites such as http://www.tibet.net or http://www.voanews.com may find themselves redirected to computers in Korea, Azerbaijan, the US or China itself. While these addresses vary across the country, there are cases of correlation. DNS servers in different cities, operated by different ISPs, will quite often redirect to the same incorrect IP addresses. A quick analysis of these shows a range of relatively innocent-looking systems that seem to have been plucked more or less at random.

One of the more interesting examples was looking at the redirection surrounding the Tor Project’s website: https://www.torproject.org. Tor is a well-known target of filtering in China, so it isn’t surprising that they are being DNS poisoned. What was interesting, however, was finding that across China more than 14 separate servers all redirected https://www.torproject.org to a website owned by “The Pet Club”, a Florida-based pet-grooming service. When New Scientist magazine wrote a short article on this work recently, they contacted the webmaster of http://www.thepetclubfl.net to get his thoughts. The most interesting result of that conversation was that The Pet Club do experience a high volume of traffic from Chinese users, showing that the relevant IP address is not blocked. This was by no means the only example of such behaviour.

If we question why this all happens we are clearly moving from facts to speculation, but here are my theories for this strange behaviour:

- DNS poisoning by returning incorrect IP addresses results in a connection to the (fake) site. Assuming that these are likely to be outside of China, this means that Chinese border routers will observe connections to these IP addresses, which are unlikely to be visited by average Chinese users. Therefore it will be possible to observe users trying to get to https://www.torproject.org while still blocking their attempts. Simply returning ‘no such domain’ would effectively block many users, but would not reveal the scale of the connection attempts.

- The correlation of IP addresses shows some level of central decision-making. My theory is certainly that a large amount of the filtering decisions come in the form of guidelines rather than strict rules, resulting in variations as the guidelines are implemented by local ISPs and organisations. Despite this, there do seem to be situations where stronger rules are sent. The Pet Club case, for example, could feasilbly be explained by an instruction to ‘redirect the Tor Project’s website to thepetclubfl.net’, which was then inserted into local DNS servers.

What I find fascinating in this work is the complexity of blocking. We can study DNS redirection, IP blocking, keyword filtering, BGP manipulation, and social media takedown, but this is just a technical angle. On top of this we have variations from location to location, variation over time, the choice of what method to use for particular blocking targets, and now whether or not to send precise blocking commands or more flexible guidelines.

I have many plans to extend this work to the rest of the world, and to produce similar high-resolution testing for IP reachability and other forms of filtering while still avoiding the need to involve individuals on the ground. What this study of DNS filtering shows is that the overall story of the filtering is far more complicated than simply asking what websites are blocked in which countries.

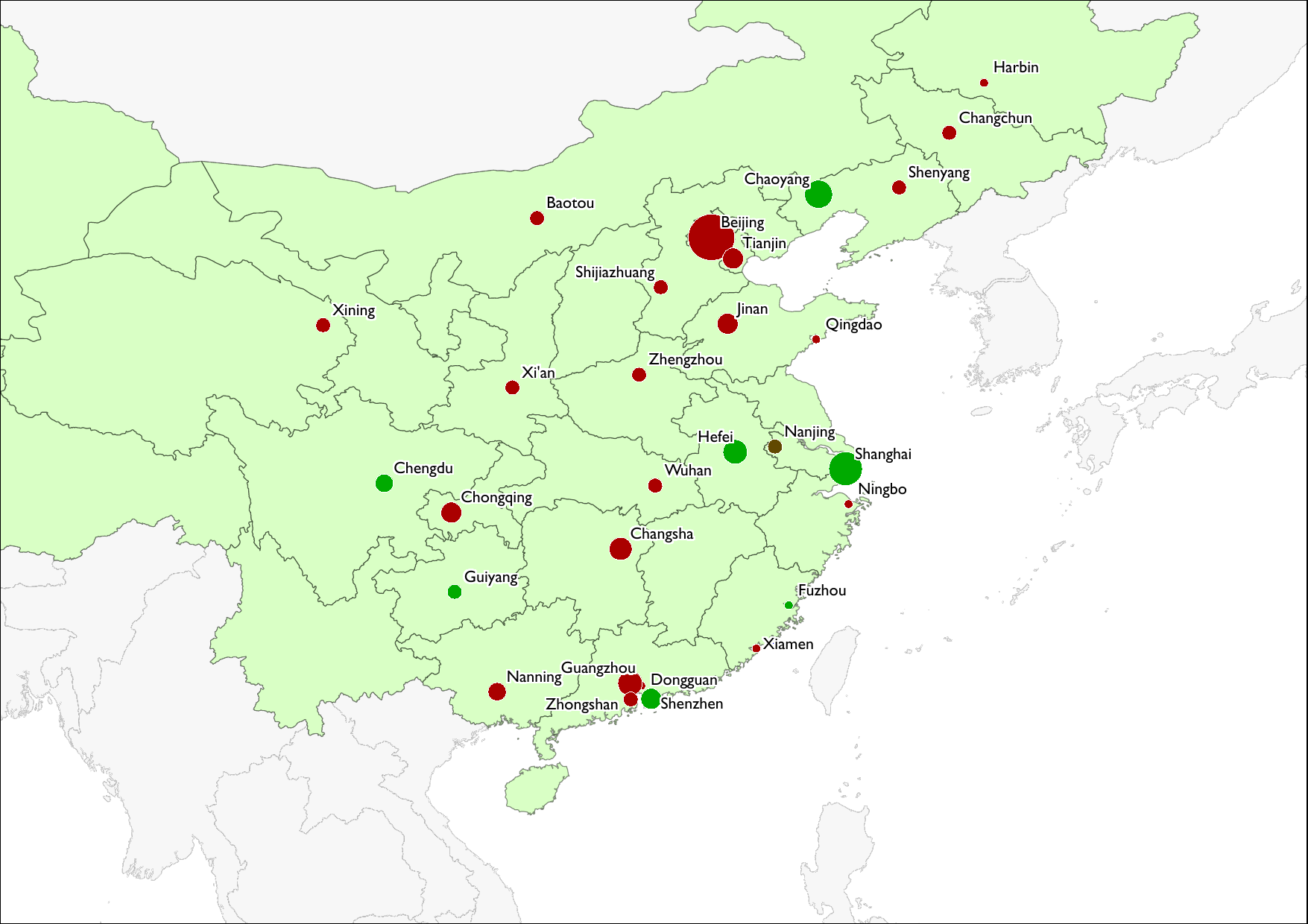

Just to conclude: a diagram of the IP redirection poisoning seen for China as of September 2012. The scale runs from green to red, with red showing more DNS redirection for censored sites and green showing less. Size of circles indicate the number of results available, in terms of the number of servers, for a given city.